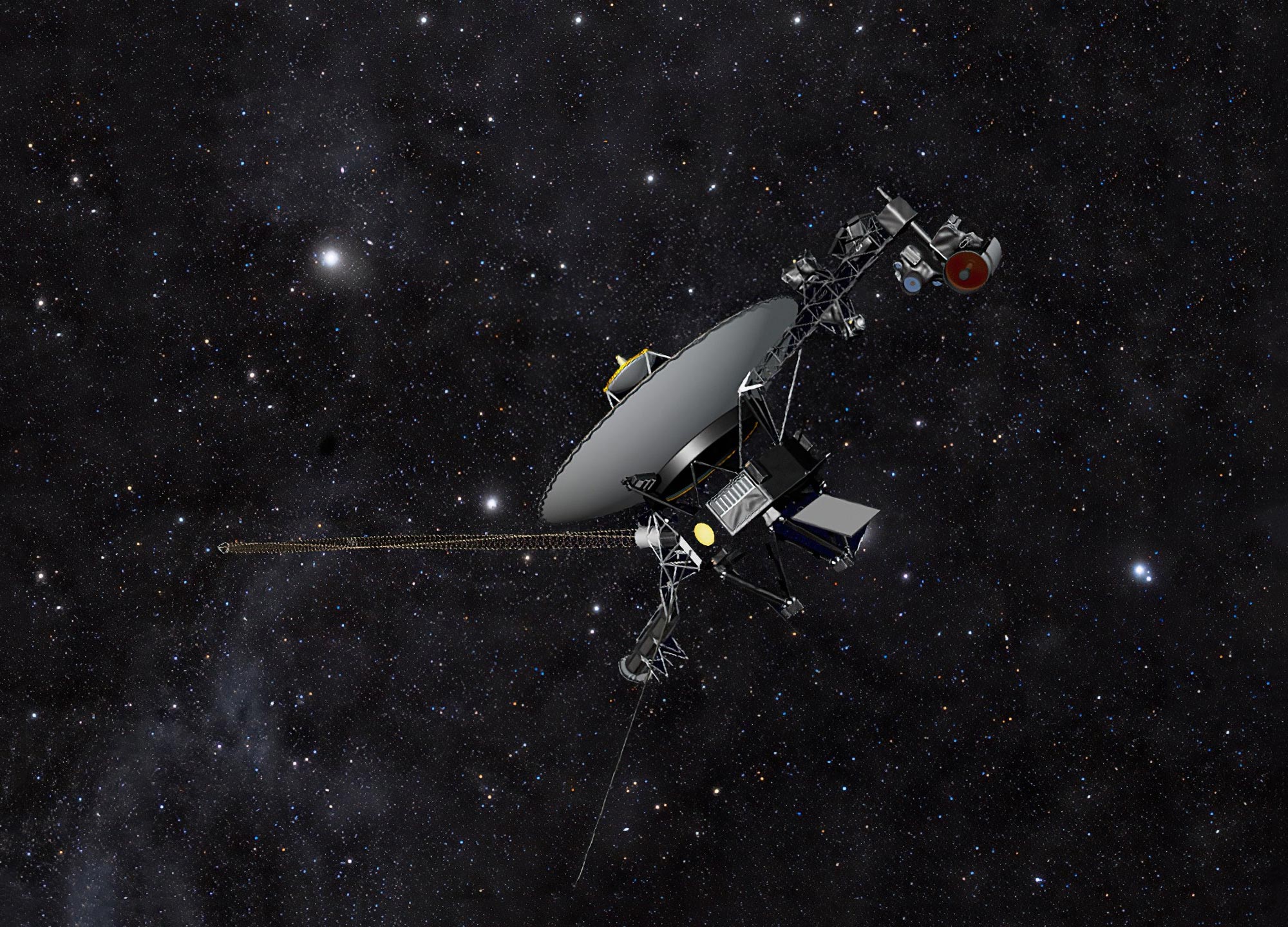

Das Konzept dieses Künstlers zeigt die NASA-Raumsonde Voyager vor einem Sternenfeld in der Dunkelheit des Weltraums. Die beiden Voyager-Raumsonden entfernen sich auf einer Reise in den interstellaren Raum immer weiter von der Erde und werden schließlich das Zentrum der Milchstraße umkreisen. Bildnachweis: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Der Plan sieht vor, dass die wissenschaftlichen Instrumente von Voyager 2 einige Jahre länger als bisher erwartet in Betrieb bleiben und so mehr Entdeckungen aus dem interstellaren Raum ermöglichen.

Die 1977 gestartete Raumsonde Voyager 2 ist mehr als 20 Milliarden Kilometer von der Erde entfernt und nutzt fünf wissenschaftliche Instrumente zur Untersuchung des interstellaren Raums. Um den Betrieb dieser Instrumente trotz schwindender Stromversorgung aufrechtzuerhalten, begann das alternde Raumschiff, einen kleinen Reservestromspeicher zu nutzen, der als Teil eines Sicherheitsmechanismus an Bord vorgesehen war. Der Schritt würde es der Mission ermöglichen, die Schließung eines wissenschaftlichen Instruments bis 2026 statt dieses Jahr zu verschieben.

Das Ausschalten eines wissenschaftlichen Instruments reicht nicht aus. Nach der Abschaltung eines Instruments im Jahr 2026 wird die Sonde weiterhin vier wissenschaftliche Instrumente mit Strom versorgen, bis eine niedrige Stromversorgung die Abschaltung eines anderen Instruments erfordert. Wenn Voyager 2 gesund bleibt, geht das Ingenieurteam davon aus, dass die Mission noch viele Jahre andauern wird.

Das Voyager-Testmodell, das 1976 im Weltraumsimulationsraum des JPL ausgestellt wurde, war eine exakte Nachbildung der 1977 gestarteten Zwillingsraumsonden Voyager. Die Vermessungsplattform des Modells erstreckt sich nach rechts und enthält mehrere der wissenschaftlichen Instrumente des Raumfahrzeugs, die bei der Veröffentlichung verwendet wurden . Positionen. Bildnachweis: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Voyager 2 und ihr Zwilling Voyager 1 sind die einzigen beiden Raumschiffe, die außerhalb der Heliosphäre operieren, der schützenden Blase aus Partikeln und Magnetfeldern, die von der Sonne erzeugt werden. Die Sonden helfen Wissenschaftlern bei der Beantwortung von Fragen zur Form der Heliosphäre und zur Rolle beim Schutz der Erde vor energiereichen Teilchen und anderer Strahlung in der interstellaren Umgebung.

sagte Linda Spilker, Voyager-Projektwissenschaftlerin[{“ attribute=““>NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, which manages the mission for NASA.

Power to the Probes

Both Voyager probes power themselves with radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs), which convert heat from decaying plutonium into electricity. The continual decay process means the generator produces slightly less power each year. So far, the declining power supply hasn’t impacted the mission’s science output, but to compensate for the loss, engineers have turned off heaters and other systems that are not essential to keeping the spacecraft flying.

With those options now exhausted on Voyager 2, one of the spacecraft’s five science instruments was next on their list. (Voyager 1 is operating one less science instrument than its twin because an instrument failed early in the mission. As a result, the decision about whether to turn off an instrument on Voyager 1 won’t come until sometime next year.)

Each of NASA’s Voyager probes are equipped with three radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs), including the one shown here. The RTGs provide power for the spacecraft by converting the heat generated by the decay of plutonium-238 into electricity. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

In search of a way to avoid shutting down a Voyager 2 science instrument, the team took a closer look at a safety mechanism designed to protect the instruments in case the spacecraft’s voltage – the flow of electricity – changes significantly. Because a fluctuation in voltage could damage the instruments, Voyager is equipped with a voltage regulator that triggers a backup circuit in such an event. The circuit can access a small amount of power from the RTG that’s set aside for this purpose. Instead of reserving that power, the mission will now be using it to keep the science instruments operating.

Although the spacecraft’s voltage will not be tightly regulated as a result, even after more than 45 years in flight, the electrical systems on both probes remain relatively stable, minimizing the need for a safety net. The engineering team is also able to monitor the voltage and respond if it fluctuates too much. If the new approach works well for Voyager 2, the team may implement it on Voyager 1 as well.

“Variable voltages pose a risk to the instruments, but we’ve determined that it’s a small risk, and the alternative offers a big reward of being able to keep the science instruments turned on longer,” said Suzanne Dodd, Voyager’s project manager at JPL. “We’ve been monitoring the spacecraft for a few weeks, and it seems like this new approach is working.”

The Voyager mission was originally scheduled to last only four years, sending both probes past Saturn and Jupiter. NASA extended the mission so that Voyager 2 could visit Neptune and Uranus; it is still the only spacecraft ever to have encountered the ice giants. In 1990, NASA extended the mission again, this time with the goal of sending the probes outside the heliosphere. Voyager 1 reached the boundary in 2012, while Voyager 2 (traveling slower and in a different direction than its twin) reached it in 2018.

More About the Mission

Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), a division of Caltech in Pasadena, built and operates the Voyager spacecraft. The Voyager missions are a part of the NASA Heliophysics System Observatory, sponsored by the Heliophysics Division of the Science Mission Directorate in Washington.

„Zertifizierter Unruhestifter. Freundlicher Forscher. Web-Freak. Allgemeiner Bierexperte. Freiberuflicher Student.“

More Stories

Die Federal Aviation Administration fordert eine Untersuchung des Misserfolgs bei der Landung der Falcon-9-Rakete von SpaceX

Identische Dinosaurier-Fußabdrücke auf zwei Kontinenten entdeckt

SpaceX startet 21 Starlink-Satelliten mit einer Falcon 9-Rakete von Cape Canaveral aus – SpaceflightNow